Rem Koolhaas Biography and Photos

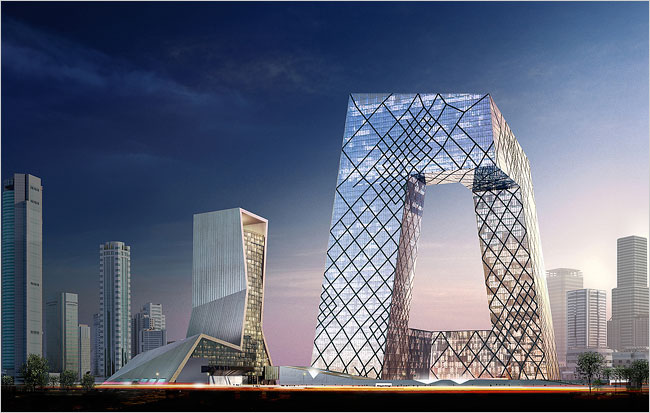

Rem Koolhaas is considered by his many followers to be the coolest, hippest, and most cutting-edge architect on the planet. But, like all things cutting-edge, Koolhaas is difficult to classify. Since the late 1970s the Dutch designer has earned acclaim as an author, a theorist, an urban planner, a cultural researcher, and a professor at Harvard. And, of course, he has amassed an array of projects ranging in size from small—The Bordeaux House (1998)—to large—the CCTV Headquarters in Beijing, China (begun 2004)—to extra large—the Euralille complex, located in Lille, France (1994). Although his projects are viewed as visionary by most, they are also unusual and frequently constructed using inexpensive, everyday materials. As a result they have been described as inspired, weird, or downright ugly. A prime example of Koolhaas's mixture of beautiful and bizarre is the Seattle Central Library, located in Washington and completed in 2004. Some consider it to be a revolutionary structure that taps into Seattle's urban energy; others call it a blight on the city skyline. Regardless, it is the largest U.S. Koolhaas project to date, and it marks the clear beginning of his American phase. And, despite his critics, there is no doubt that the breakthrough designer is changing the face of contemporary architecture. As U.S. architect Frank Gehry (1929–) told Belinda Luscombe of Time, "I would say he's the most comprehensive thinker in the profession today. He's the hope for the cities."

Rem Koolhaas was born on November 17, 1944, in Rotterdam, Netherlands, just four years after the major seaport city was destroyed by German bombing during World War II (1939–45; war in which Great Britain, France, the Soviet Union, the United States, and their allies defeated Germany, Italy, and Japan). His father, Anton, was a well-known Dutch writer and film critic, who, when Koolhaas was eight years old, traveled to Indonesia to serve as the director of a newly formed cultural institute. At the time, Indonesia had just broken ties with the Dutch, who had dominated the region since the seventeenth century. From age eight to twelve Koolhaas and his two younger siblings lived with their father in Jakarta, Indonesia. While there, the young boy developed a fascination with Asia that would continue into adulthood.

"The word 'architecture' embodies the lingering hope—or the vague memory of a hope— that shape, form, coherence could be imposed on the violent surf of information that washes over us daily."

"The word 'architecture' embodies the lingering hope—or the vague memory of a hope— that shape, form, coherence could be imposed on the violent surf of information that washes over us daily."

After returning to the Netherlands Koolhaas eventually took up journalism as a career, writing for the Haagse Post. At the same time, he began socializing with film students and even dabbled in film school for a bit. In 1969 Koolhaas co-wrote a script called The White Slave, which was produced by Dutch director Rene Daalder. In interviews Koolhaas calls this early film a commentary on modern Europe using clips from B-movies (low-budget movies). The would-be filmmaker even wrote several screenplays for Hollywood directors, which were never produced.

One day, while speaking about film to a group of architect students at the University of Delft, Koolhaas realized that what he truly wanted to do was build. Actually, the idea was not so farfetched because his maternal grandfather had been an architect, and that particular career option had always been lurking in the back of his mind. So, Koolhaas packed his bags and headed for London, where he studied at the Architecture Association School. He quickly became known for being an unconventional thinker, especially after he published several controversial papers, one of which proposed walling off portions of London and asking citizens to decide on which side of the wall they wanted to live.

One day, while speaking about film to a group of architect students at the University of Delft, Koolhaas realized that what he truly wanted to do was build. Actually, the idea was not so farfetched because his maternal grandfather had been an architect, and that particular career option had always been lurking in the back of his mind. So, Koolhaas packed his bags and headed for London, where he studied at the Architecture Association School. He quickly became known for being an unconventional thinker, especially after he published several controversial papers, one of which proposed walling off portions of London and asking citizens to decide on which side of the wall they wanted to live.

Because of his innovative ideas Koolhaas was given a Harkness Fellowship in 1972, which allowed him to study at the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies in New York City. The Harkness Fellowship is administered by the Commonwealth Fund, a charitable foundation established in 1918 by U.S. philanthropists Anna and Edward Harkness; it allows academics and artists from outside the United States to study in the country for two years. While in New York, Koolhaas trained under noted American architect Peter Eisenman (1932–) and famed German architect O. M. Ungers (1926–). The thirty-four-year-old also became enthralled by what he viewed as the dynamics of New York City. Contrary to the popular notion of the time of urban sprawl (moving to and building in the outskirts of cities), New York was jam-packed with people living in what Koolhaas termed in many interviews as "the culture of congestion."

In 1978, based on his observations, Koolhaas penned Delirious New York, which he frequently described as a "manifesto for Manhattan," and which discusses in detail patterns of urban growth. The book became an instant classic, and according to CNN.com, "Critics hailed it as a must-read on the subject of modern architecture and society." Therefore, oddly enough, before he laid a single brick on a single project the Dutch designer had achieved a level of fame that takes most architects years to achieve.

When he was traveling and studying in the United States, Koolhaas was accompanied by his wife, Madelon Vriesendorp, an architect and painter. In fact, the two were professional partners as well as life partners. The dust jacket of Delirious New York features a Vriesendorp painting, and a few years earlier, in 1975, Koolhaas, Vriesendorp, and two friends, Elia and Zoe Zenghelis, formed their own design company called the Office for Modern Architecture. Known as OMA, which happens to mean "grandmother" in Dutch, the company was originally based in London, but eventually moved to Rotterdam in the West Netherlands. Marcus Fairs of Icon Magazine described it as a "hot-house research laboratory," and in 2004 OMA employed 85 staff members, with some 1,400 hopeful architects applying for employment each year.

When he was traveling and studying in the United States, Koolhaas was accompanied by his wife, Madelon Vriesendorp, an architect and painter. In fact, the two were professional partners as well as life partners. The dust jacket of Delirious New York features a Vriesendorp painting, and a few years earlier, in 1975, Koolhaas, Vriesendorp, and two friends, Elia and Zoe Zenghelis, formed their own design company called the Office for Modern Architecture. Known as OMA, which happens to mean "grandmother" in Dutch, the company was originally based in London, but eventually moved to Rotterdam in the West Netherlands. Marcus Fairs of Icon Magazine described it as a "hot-house research laboratory," and in 2004 OMA employed 85 staff members, with some 1,400 hopeful architects applying for employment each year.

In its first decade OMA's designs were theoretical, meaning they were captured on paper but never actually built. Koolhaas submitted many striking and innovative ideas to several high-profile architectural companies and entered a number of competitions, but no one seemed interested. Finally, in 1987 Koolhaas was hired to design and build the Netherlands Dance Theater in The Hague. Composed of three areas, including a stage and auditorium; a rehearsal studio; and a complex of offices and dressing rooms, the theater garnered Koolhaas immediate acclaim. According to Koolhaas's profile featured on the Syracuse University Web site, it is considered by Phyllis Lambert of the Canadian Centre for Architecture to be one of the top nine buildings of the twentieth century.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Dear Visitor,

Please feel free to give your comment. Which picture is the best?

Thanks for your comment.